For years, at conferences and talks and in articles, I’ve been flogging writing groups as especially necessary for novelists.

The reasons are obvious. Writing a novel is lonely, and it takes a long time. You’re going to need people to read it along the way—sometimes for feedback, but mostly just to reassure you that yes it’s a real thing and yes you should keep writing because yes they want to read more. Unfortunately, no matter how enthusiastic and supportive they start out, as the years crawl by, your best friend, sibling, partner, old professor, therapist, etc. will burn out on reading and rereading your drafts. A writing group can stay in it for the long haul because of mutual returns on time and effort put in. You learn from each other, you support each other, and over time, you trust each other, even when you disagree.

But something that’s really started to gel for me since I started teaching is that whether you have one or not, writing groups are, in a way, built into the novel itself. Novel-writing is an inherently collaborative act. Even if you’re writing your novel alone with no internet in a cabin in the Yukon, you’re already participating in a group effort—not just because of the hidden support and labor of others that makes every novel possible, but because of the history of the novel itself.

Image: My writing group. (La Danse, Henri Matisse, 1910.)

In graduate school, I studied the rise of the English-language novel over three centuries. Like many closet novelists, I had first fallen in love with literature via fat 19th-century novels: Dostoevsky and Henry James were my poison. But when I began to study for the GRE Literature test,* I discovered novels I’d never read or even heard of that predated my favorite books by up to a century. Ever the anxious autodidact, I raided the cheap paperbacks at Half-Price Books and subsequently worked my way through Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, Fanny Burney’s Evelina, and (inexplicably) Elizabeth Inchbald’s A Simple Story. I can’t say I loved them all, or even understood them, really, but these 18th-century novels blew my mind nevertheless. Somehow, despite having read plenty of modernist and contemporary novels, it had never occurred to me just how much the novel had changed over time, to the point where I barely recognized its earliest iterations in English.

Early novels don’t have the smoothed-out narrative conventions we’re used to. They are episodic, like Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders; nested, like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; and often sprinkled with corroborating “evidence,” like newspaper clippings, receipts, and claims of found manuscripts, all suggesting the story you are reading might be true.

Moreover, because the profession of “novelist” didn’t really exist yet, early novels were frequently written by other types of professionals who brought their expertise to bear on their fiction. Defoe was a journalist, and his A Journal of the Plague Year can be read as either history or fiction, though it doesn’t really fit either category. Samuel Richardson was a printer, and his smash-hit epistolary novel Pamela was inspired by the how-to manuals on letter-writing he produced to help servants and workers displaced from the English countryside write their families back home. And, famously, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein began as a dream, liberally mixed with political philosophy and poetry from her upbringing as the child of two philosophers, spun out into a rambling yarn for a ghost-story contest with her friends.

Far from springing fully formed from the genius of lone imagineers, these novels were patched together, ad hoc, from bits and pieces of writing—poetry, pamphlets, newspapers, instruction manuals, gossip, sermons, letters—that were circulating at a higher rate than ever before due to innovations in printing, cheaper paper, higher literacy rates, increased mobility, and other early effects of the Industrial Revolution. In grad school we were trained to see the novel as a direct adjunct to the rise of capitalism, and that’s true. But you can also see it as a kind of palliative to capitalism—an attempt, however flawed, to restore community, continuity, and wholeness to an increasingly fragmented and uprooted society.

The novel in English came about because sexually harassed servant girls needed to write their parents for comfort and advice; because liberated teen girls needed to upstage their big-shot poet boyfriends; because workers needed to while away the lonely hours away from home. With the breakdown of old hierarchies and institutions, people craved new origin stories and parables, representations of the past and imaginations of the future. Novels served as thought experiments, guides to social etiquette, cautionary tales, and chronicles of the diversity and variety of city life. They were a new form of community.

Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian literary critic from the 1930s whose work was suppressed during the Soviet era, famously argued that the novel is inherently dialogic—carrying on a perpetual dialogue with existing literature and language, constantly quoting other texts and genres directly and indirectly—and polyphonic—capable of digesting and representing widely divergent voices, viewpoints, genres, and modes of knowledge and speech, all without losing its form as a novel.**

As a working novelist, this still seems like a remarkably good definition of the novel to me. Even and especially now, during an unprecedented explosion of newly accessible information, the novel continues to rapaciously digest everything that comes in its way. Think of the way autofiction appropriates and repurposes memoir, or how Gone Girl tricked the reader with faked journal entries, or Fifty Shades starting as fan-fiction. (And if that last is too lowbrow, think of the highbrow equivalent—literary novels that rewrite famous novels from a marginal character’s point of view. Historical fiction about authors can also verge on fan fiction at times.)

You can take or leave these examples, but to me, they are resounding proof that the novels we read and write continue to be defined by the way they stitch together a multiplicity of voices, an ever-increasing ocean of stories and knowledge and the sheer content we consume. Books, movies, social media, true crime, ads, therapy speak, course readings, family histories, cultural legends, emails from friends, and even the genre labels that decide where books are shelved in a bookstore—ALL of these things are in the room with us when we create our beloved novels. They are patchwork, not whole cloth; they are Frankenstein’s monster jolting to life, not Athena springing fully formed from the head of Zeus.

We are never alone.

Image: The Birth of Minerva, Rene Antoine Houasse, before 1688. What we think novels are.

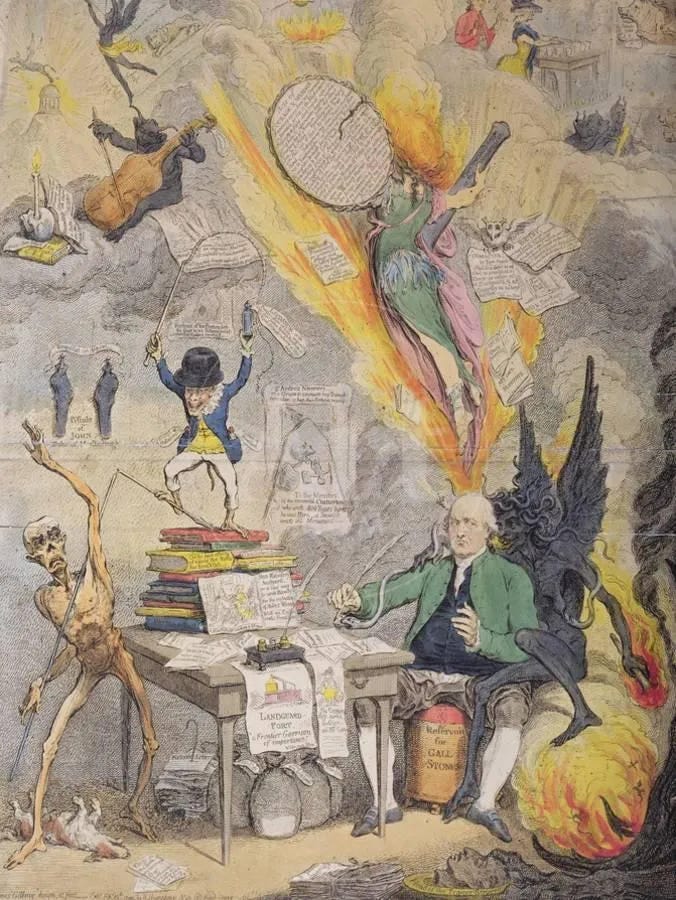

Image: Lieut. Goverr. Gall-Stone inspired by Alecto, or The birth of Minerva by James Gillray, 1790. What novels actually are.

Of course, not all of those voices are helpful. There’s also the voice of the critic, which we struggle to turn off. There’s the voice of the marketplace, and of social media, which on some days can seem like wall-to-wall book deals and literary prizes for people who aren’t you. You can turn those voices down, but, because the novel is a social form, you will never—and perhaps should never—get rid of them entirely. Your creativity flows from you, and is unique to your being, but the external form it takes is more like the Tower of Babel.

Image: The building of the tower of Babel (Genesis 11:3-5), Pieter Brueghel the Elder, 1568.

So what I’m saying is, you already have a writing group. Use it.

My writing group has a lawyer, a journalist, a theater MA, a nonprofit staffer, and an ex-academic, writing in five different genres. We are lots of other things as well (Ranger! Barbarian! Magician! Thief! Acrobat!), and in our ten years together those forms of knowledge have pooled and bounced off each other and created novels that couldn’t have existed otherwise. When students read their work in class, I hear the polyphonic clamor in their novels, as well—emails! text exchanges! a poison-pen restaurant review!—and relish the dialogues that inevitably start as classmates start to contribute their various forms of expertise.

If novels are collaborative, then they are also, in a sense, communities in the process of creation. To witness this in real time, I recommend reading unfinished work aloud in a writing group or class—something else I tout for novelists in particular. When the normal boundaries of time and distance between writer and reader are collapsed, the dialogic quality of the novel really sings. Experiencing a novel this way has given me an alternate way of thinking about writing groups, not just as sites for investment and return, but as places where novels can become communities. And that, in itself, is a beautiful thing.

*Now defunct, and almost certainly for the best.

**Of course, these same qualities make the novel a perfect vehicle for imperialism. Conversations around cultural appropriation are constantly renegotiating and relitigating this problem, as they should. Maybe I’m naive, but I tend to think that the novel as a form is fully capable of digesting, representing, and honoring this discourse—witness R. F. Kuang’s Yellowface, for example.

Loved this celebration of the novel AND writing groups. When people ask me the secret to writing a book, I always say A WRITING GROUP.

Love this so much!