How do you approach/handle writing about things that are true but might be hard for others to digest? So much of my writing concerns truths that others struggle to grapple with. It's easy for me to hold space for hurt feelings about scientific truths (e.g., from a deeply religious person who takes exception to the assertion that evolution is a fact), but it's a bit harder when the things I want (need?) to write about intersect directly with others' lives and feelings. Writing truthful things about myself means writing things about my experience of my mother, father, siblings, friends, and colleagues, and inherently about the communities in which they/we/I live. [emphasis mine.] I don’t suppose it matters whether one writes fiction or nonfiction: someone we know will read what we wrote, and I wonder what your take is on how one best processes that.

Dear Truthful,

I hope you don’t mind my giving you a pseudonym! I did it for a reason, and not just because I know you personally and knew you probably wouldn’t mind.

The truth is, Truthful, that I got way up in my head about my first Dear Scribbler letter. After I wrote it, I panicked a little. Advice is 90% projection and 10% delusions of grandeur. The imposter syndrome was strong.

But then again, that last question was the deep end of the pool. I decided that, as a palate-cleanser, I’d do a quick, low-stakes question next. And then I realized that quick, low-stakes questions have right-or-wrong answers, and I don’t always know those answers. So then I was in this predicament where I didn’t want to answer a big scary letter with sweeping advice that might affect someone’s life, and I didn’t want to answer a small concrete letter because I didn’t want to get it wrong. And then a hailstorm knocked a hole in my car, and I got sick, and my cat got sick, and my kid got sick, and I got sick again—four! different! kinds! of! sick!—and I just gave up for a while.

When I was ready to write again, this was the letter that pulled me back in, for the simple reason that truth is a messy bitch, and I like messy.

Image: Truth coming from the well armed with her whip to chastise mankind, Jean-Leon Gérôme, 1896. MESSY.

To get going again, I gave myself the advice I often give clients. It’s advice for writing novels, voiced by the fictional narrator of Muriel Spark’s A Far Cry from Kensington, but there’s a clear application here:

Now, it fell to me to give advice to many authors which in at least two cases bore fruit. So I will repeat it here, free of charge. It proved helpful to the type of writer who has some imagination and wants to write a novel but doesn’t know how to start.

‘You are writing a letter to a friend,’ was the sort of thing I used to say. ‘And this is a dear and close friend, real – or better – invented in your mind like a fixation. Write privately, not publicly; without fear or timidity, right to the end of the letter, as if it was never going to be published, so that your friend will read it over and over, and then want more enchanting letters from you.

When stuck between “no one will ever read this” (the void) and “this must be good enough to please every person I’ve ever met as well as people who haven’t been born yet who will read it for a post-pandemic lit survey” (the panopticon), it can be extremely helpful to manufacture a friendly audience of one in your head and write only to them. An ideal reader, but a specific ideal reader—a friend you want to delight and impress, but one who already loves you and your work. Write to that friend.

An advice column has a built-in ideal reader—the advice-seeker. Isn’t that nice and obvious? So, with that in mind, I decided to write this as a letter TO you, Truthful. I had to make up a name for you in order to do it, so I did. I hope you like it. I know you, and so I know it to be a truthful name.

Image: Dame Muriel Spark, (1918-2006), by Alexander Moffat. Listen to Auntie Muriel.

Now for your answer. It is not unrelated!

When you write, you close all the windows and sit inside your heart alone. If there were someone in there with you, you wouldn’t have to write. You’d just talk. But there’s never someone with us all the time. We write to fill the silence in that smallest, loneliest chamber. What comes out may be a cry for recognition, a testimony, a doodle, an homage, a sigh of boredom, an act of resistance. But it is also, in some way, an act of love.

To write about any subject is to lavish it with attention and care. The amount of time and energy required to take an experience and put it through the machine of your brain and make it come out the other side as a sentence is tremendous. Whether it’s a childhood trauma or a fucked-up political situation or an only medium-fucked-up relationship, to write about it as truthfully as possible, the only way you can, which is to say, filtered through your own subjective experience or life, is to sit with it and inside it for a long, uncomfortable time. This is no small thing. We say the truth hurts, but we don’t always say whom it hurts.

Who are you protecting when you shy away from writing about someone who hurt you? Is it the person you love, who did the best they could and only treated you poorly because of their circumstances? Or is it the small child who was treated poorly by that someone, and who needs, on some level, to tell themselves it couldn’t possibly have been that bad, or that there had to be extenuating circumstances, because otherwise, the rejection will hit all over again, as fresh as it did before empathy rushed in to soften it? In other words, are you protecting you?

So we’re clear, it is fine to choose not to write what hurts you. Your health and happiness are worth more than any book. But. Given that you’ve set out to write this one, consider listening to it. Consider that the book may be telling you its entire raison d’être was to get you to experiment with the thought crime of believing your own story over someone else’s version of it—or over a version you’ve made up for them, to protect their image from some imagined desecration.

Here’s the thing. You already carry this truth in your heart. You have spent a lifetime not writing it. At this point, you’re trying not to think of an elephant.

I can hear in your question that you already know you must be truthful, Truthful, or not write at all—at least, not this particular book. That’s an option worth considering. But consider the strong possibility that everything you write is going to try to point you back toward this particular elephant. That even if you try to write a book about how to start your own candy-making business, you will wind up back at the elephant’s doorstep, wondering whether this time you’ll actually knock.

Just write about the elephant.

You don’t have to publish it. You don’t have to show anyone. You don’t have to look at it ever again. You can put it in a file clearly labeled “junk I hate.” Just write the words.

You are a long way from someone else reading this. There is plenty of time to invite nuance and perspective into the picture. By the time you publish something unflattering, you will have devoted so much care and attention to them as a character that chances are, they’ll get their due. But if you don’t give yourself your due first, there will never be any truth to add nuance to.

And that’s okay, if that happens! Every story demands the truth, but not every story demands every truth. If there are truths you won’t write, then you must find a story that doesn’t demand that particular truth from you. Better not to write about something at all than to write a lie.

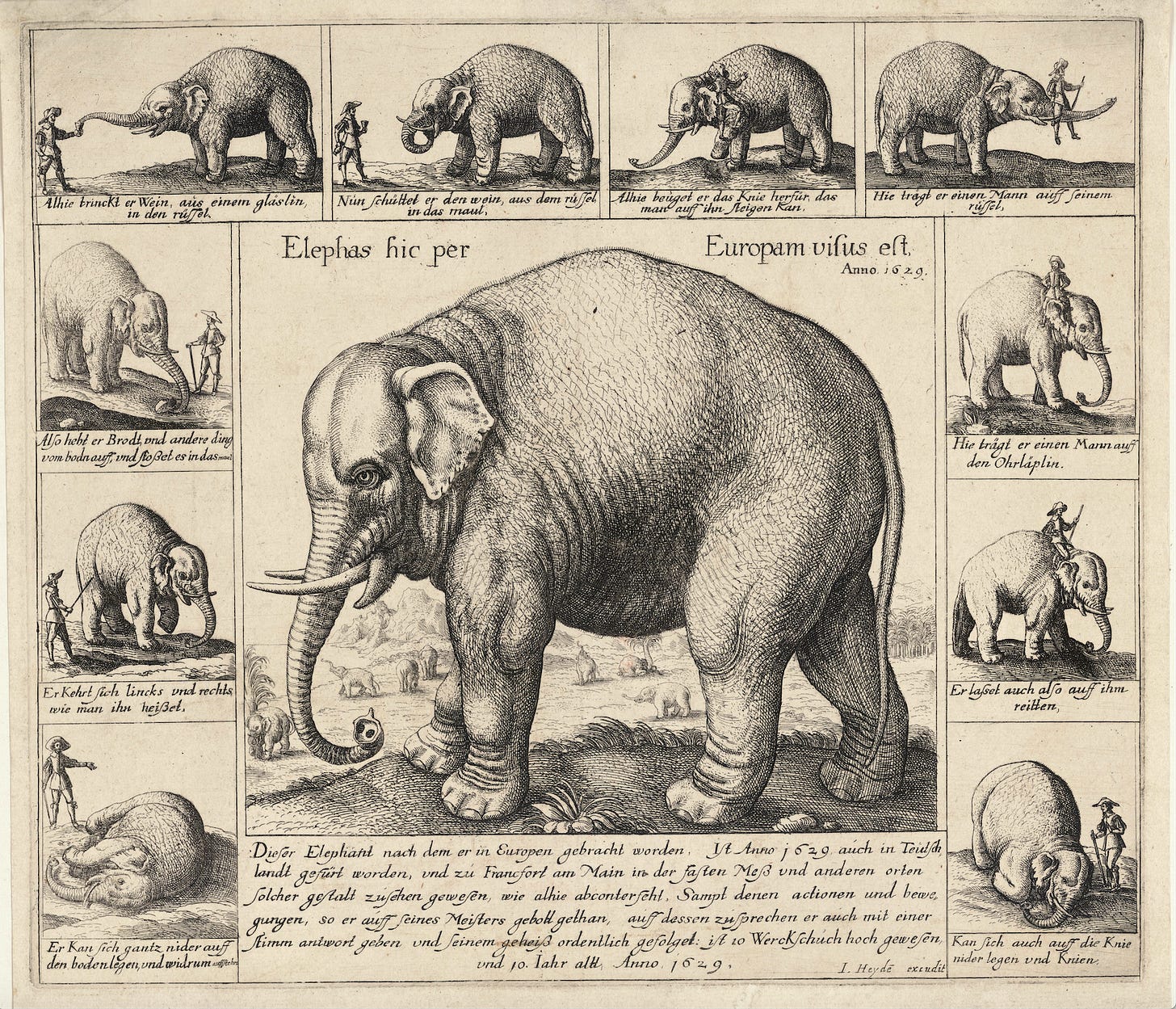

Image: Don Diego performing tricks in Germany in 1629, Wenceslas Hollar. AKA, Cruelty to elephants.

But, okay. Let’s fast-forward years from now. The book gets published, with unflattering details about a real person in it. Details that person could read; and, in the case of a memoir, almost certainly will read. And those details might hurt.

Once I wrote a book in which the narrator kills a character inspired by a real-life person I once knew. This is just Crime Writing 101, to be honest. If you write about murder, and you use people you’ve known for character inspiration (and we all do, sorry), it will inevitably come to pass that you “kill” someone you know or knew. Crime writers all joke about this, but under the jokes lies an acknowledgment that writing fiction is a complicated and messy cognitive business that draws on all parts of ourselves, not all of them pleasant.

So anyway, after the book came out, this person died. In real life. It turned out they had cancer. To make matters worse, the character I had written also had cancer at the time of their death.

Some mutual acquaintances reached out to ask if I had known they were sick when I wrote that. In case it’s unclear, there is no world in which I would bait someone with cancer by killing off a fictionalized version of them with cancer. I cannot imagine being that cruel.

But wasn’t my depiction of this person already cruel?

Yeah. It was. I’m cruel to all my characters, but I was extra cruel to that one.

It wasn’t the murder that was cruel—that part, obviously, was made-up—or the tarty genre bits, or even the cancer, which only coincided with the truth by accident. The cruelest parts were the stringently truthful ones. On the day they died, each and every of those truths came back to haunt me.

A friend of mine talked me down, and I am going to pass their words along to you:

“First of all, you didn’t kill anyone. That’s preposterous,” they said. “Second of all, if a person can be killed by hearing the truth—well, maybe it was that person’s time to go.”

Maybe that’s just something all writers need to hear periodically to feel better about the fact that we are, as Joan Didion famously said, always selling someone out. The truth is, after all, a messy bitch. (Like Didion herself.)

But with all due respect: Who are we selling out when we don’t write?

It’s highly unlikely that you telling your truth will permanently destroy something. But. BUT. Just in case it does (or something else does, and you are tempted to take that on yourself):

Communities that can be destroyed by the truth are in need of destroying. Relationships that can be destroyed by the truth are in need of a major overhaul. People who can be destroyed by hearing the truth about their effects on others need more than you can give them by not telling it.

Image: An Allegory of Truth and Time (1584–85) by Annibale Carracci

I don’t believe every truth needs to be told to every person. Behavior is deemed bad or good, criminal or laudable, within a particular social-historical context; villains and victims are the same people at different moments of their lives, in different settings; and the truth about why people behave badly is so much crueler than the fictions we spin about it that we had to make up the concept of evil to guard ourselves against the crushing weight of that cruelty.

But that doesn’t make the truth any less true.

I have no idea whether that person read my book (I suspect not). But many of their former students did. They contacted me in private to say they recognized their truth in what I had written, felt seen and cared for and sometimes even a tiny bit healed by it. In a way I am hard pressed to explain, writing that character was an act of love—not just for those people, and for myself, but even for the person themself. I had to love them in order to write them truthfully.

I know you will be able to do that, Truthful.

How to approach it? With care. How to handle it? The same way you’d handle someone else telling you the truth—by listening to them, believing them, and letting them finish the whole thing without interrupting. How to process it? With compassion and comfort for yourself: a warm blanket, a hot bath, a favorite song, a popsicle. Write your truth like a letter to a dear friend who wants—no, desperately needs—to hear it. Write it for someone who is starving for it. I guarantee she’s out there.

It’s like you read my mind today.

So much worth sharing here. ♥️. And that painting of Truth coming out of the bath. Wow!